CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs and ZFNs - the battle in gene editing

Technological advances are crucial for innovative biological research. ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/CRISPR-associated Cas have revolutionized genome editing.

Advances in DNA genome editing

Genome editing is the process of making permanent modifications to DNA sequences at specific locations. Genomic editing was initially performed by introducing breaks to double-stranded DNA via radiation or using cleavage proteins called endonucleases. DNA was repaired either by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), where the broken ends are directly joined back together, or by homologous repair (HR) where a homologous (similar) DNA sequence of is used as a guide for repair. Repair templates may also contain selection markers, such as those for antibiotic resistance or fluorescent tags; these selection tools can be used to screen mixed populations of cells for those containing the desired DNA modifications.

The genome editing process until recently, was time-consuming, requiring mutagenesis, cleavage, and the synthesis and delivery of long homologous repair DNA templates for specific changes. Genome editing in mammalian cells was often inefficient and required multiple steps. Fortunately, the discovery of novel nucleases allowed improvements and advances in the field of genomic editing. In this article, we will briefly describe the four groups of genome-editing nucleases: meganucleases (MNs), zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and CRISPR-associated nucleases (CRISPR-Cas9).

The era of nucleases in genome editing

-Meganucleases (MNs) are Double-stranded DNAses (enzymes that cleave DNA) with characteristically long recognition sites, for example, upward of 40 nucleotides1 (Table 1).

Meganucleases are often referred to as “DNA scissors”, due to their ability to recognize and cleave large pieces of DNA. Meganucleases are encoded by mobile introns, and their targets are found in homologous genes that lack the mobile intron they carry. First, the meganucleases pair with a recognition sequence and cleave DNA, then the mobile genetic element is inserted into the cut site2. The benefits of using meganucleases include their low toxicity in mammalian cells, as they’re naturally occurring. Another benefit is their high specificity due to their long recognition sequences, which are often not duplicated in the genome due to their large size.

- Zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs). These are based on zinc finger proteins, a family of naturally occurring transcription factors, fused on an endonuclease Fok3.

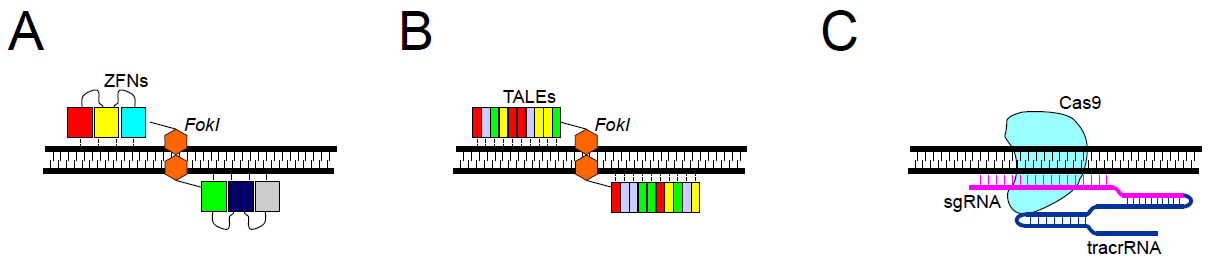

Zinc finger nucleases were one of the first enzymes utilized in targeted genome engineering and are created when a zinc finger is fused to a restriction endonuclease, usually FokI3. Zinc finger domains recognize a three base pair sequences on DNA; a series of linked zinc finger domains can therefore recognize longer DNA regions, providing desired on-target specificity. The FokI endonuclease works as a dimer, which means that the double-strand DNA cleavage occurs only at sites of binding of two ZFNs onto the opposite DNA strands (Figure 1A). Two ZFNs are engineered to recognize different closely located nucleotide sequences within the target site, which requires the simultaneous recognition and binding of both ZFNs, and naturally limits off-target effects. However, multiple zinc finger motifs aligned in an array also influence the specificity of neighboring zinc fingers, making the design and selection of modified zinc finger arrays more challenging. Predicting specificity of the final product is can often be difficult.

- Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) are fusion proteins of a bacterial TALE protein and the FokI endonuclease4.

Similar to ZFNs, target specificity comes from the protein-DNA association. In the case of TALENs, a single TALE motif recognizes one nucleotide, and an array of TALEs can associate with a longer sequence (Figure 1B). The activity of each TALE domain is restricted only to one nucleotide and does not affect the binding specificity of neighboring TALEs, making the engineering of TALENs much easier than ZFNs. Like ZFNs, TALE motifs are linked with FokI endonuclease, which requires dimerization for the cleavage to occur. This means that the binding of two different TALENs at opposite strands in close vicinity to the target DNA is needed.

-The CRISPR-Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) system is based on the bacterial immune system.

It is composed of Cas9 nuclease and two types of RNAs: trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) and a single guide RNA (sgRNA) that recognizes the target sequence by standard Watson-Crick base pairing. It has to be followed by a DNA motif called a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). Each Cas9 protein has a specific PAM sequence,5,6 e.g., for standard Cas9 it is 5’-NGG-3’. DNA cleavage is performed by Cas9 nuclease and can lead to a double-strand break in the case of a wild-type enzyme, or to a single-strand break when using mutant Cas9 variants called nickases (Figure 1C). Recognition of the DNA site in the CRISPR-Cas9 system is controlled by RNA–DNA interactions. This offers many advantages over ZFNs and TALENs, including easy design for any genomic targets, easy prediction regarding off-target sites, and the possibility of modifying several genomic sites simultaneously (multiplexing). Furthermore, the recognition sequence of the sgRNA is small (20bp), which is useful for cloning, compared to traditional homologous repair design.

Mutations to the Cas9 protein are also used for different applications of experimental design. One example is dCas9, which that renders Cas9 catalytically dead (no activity in both catalytic domains). Many Cas9 systems, however, often achieved low off-target effects at the cost of target specificity. One means to resolve these issues, Cas9 ‘nickases’ were developed. Cas9 d10A and H840A are two mutations that render one of the domains inactive, in Cas9, such that the enzyme is only capable of single-strand DNA cleavage, compared to the double-strand cleavage of WT Cas9. The Cas9 nickases are often used in pairs, creating a double-strand break only where each nickase cleaves at each single-strand, enhancing both specificity and reducing off-target effects7.

| Feature | MN's | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

| Length of recognized DNA target | ~14-40bp | 9–18 bp | 30–40 bp | 22 bp + PAM sequence |

| Mechanism of target DNA recognition |

Protein-DNA |

DNA–protein interaction | DNA–protein interaction | DNA–RNA interaction via Watson-Crick base pairing |

| Mechanism of DNA cleavage and repair | Double-strand break | Double-strand break induced by FokI | Double-strand break induced by FokI | Single- or double-strand break induced by Cas9 |

| Design | Difficult due to the large sizes of the recognition sites which leads to a limited number to work with | Challenging. Available libraries of zinc finger motifs with pre-defined target specificity, but zinc finger motifs assembled in arrays can affect specificity of neighboring zinc finger motifs, making the design challenging. | Easy. TALE motifs with target specificities are well defined. | Easy. SgRNA design based on complementarity with the target DNA. |

| Cloning | Requires the use of the I-CreI or I-SceI scaffold | Requires engineering linkages between zinc finger motifs. | TALEs do not require linkages. Cloning of separate TALE motifs can be done using Golden Gate assembly5. | Expression vectors for Cas9 available. SgRNA can be delivered to cells as a DNA expression vector or directly as an RNA molecule or pre-loaded Cas9-RNA complex. |

Table 1. Target specificity, mechanism of action, and experimental design for commonly used editing nucleases.

Figure 1. Editing nucleases. A. ZFNs – two discrete ZFNs recognize and bind to specific sites at opposite DNA strands; assembled FokI dimer specifically cleaves target DNA. B. TALENs – two discrete TALENs recognize and bind to specific sites at opposite DNA strands; assembled FokI dimer specifically cleaves target DNA. C. In the CRISPR-Cas9 system, the DNA site is recognized by base complementarity between the genomic DNA and sgRNA, associated with tracrRNA, and loaded into Cas9 nuclease, which performs DNA cleavage.

Reducing off-target effects

The design of editing nucleases in a way that reduces off-target effects was a major issue not only for the basic science approaches, but also for their putative clinical and industrial use.

The delivery of ZFNs and TALENs, either in vivo or in vitro, can lead to toxicity or lethality due to binding at off-target sites and the induction of undesired DNA cleavage. Mutations in FokI in the case of ZFNs and TALENs were eventually introduced to promote FokI endonuclease activity only during heterodimerization events at sites bound by two discrete nucleases9,10. Off-target cleavage of CRISPR-Cas9 systems mostly comes from the recognition of fully or partially complementary genomic sites by sgRNAs11. Various approaches have been suggested to limit off-target cleavage, including limiting the amount and time of active Cas9 protein in cells by selective delivery methods or by altering Cas9 half-time12. A number of Cas9 variants with lower off-target specificity have been developed, including HF-Cas9, eCas9, and HypaCas913–15. New variants of Cas9 and Cas9 homologs, such as CRISPR-Cas12 (Cpf1) and CRISPR-Cas13a (C2c2), can recognize different PAMs, not only significantly increasing options for precision genome editing, but also potentially having higher on-target specificity16. An interesting alternative is a Cas9 fusion with FokI nuclease, which combines the advantages of ZFNs/TALENs and the CRISPR-Cas9 system16,17. When fused to the FokI endonuclease, dCas9 has greater specificity compared to Cas9 alone7. This specificity comes from the dCas9-FolkI cleavage activity, which depends strictly on the sgRNAs. The dCas9 protein proves to be a viable means to control gene expression by interfering with transcription18.

Cas9 chimeras as novel research tools – not only for DNA cleavage

Various Cas9 chimeras, including loss-of-function and gain-of-function studies, have also been recently developed19. Cas9 allows for genomic targeting, while the fused proteins can modulate Cas9 activity.

- CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), occurs when a Cas9 protein is fused to a transcriptional effector such as the repressive KRAB domain, allowing downregulation of gene expression by transcriptional repression20. This approach provides an advantage over standard RNA interference (RNAi) techniques and allows for investigation of the function of non-protein coding genes. Additionally, the opposite approach (CRISPR activation, CRISPRa) is possible, meaning Cas9 can be used to activate gene expression. For example, Cas9 fusion with transcriptional activation domains (e.g., VP64) leads to increased expression of the desired genomic loci. Additional activation of transcription can be achieved with synergistic activation mediator (SAM), where the Cas9 fusion contains several activation domains to maximize activation efficiency21. Some Cas9 chimeras do not possess nuclease activity. For example, Cas9 fusions with chromatin-modifying enzymes are used in epigenome studies to visualize protein-DNA binding sites, to examine chromatin structure, or for histones post-translational modification research22,23.

CRISPR-Cas9 and cell line gene-editing innovations

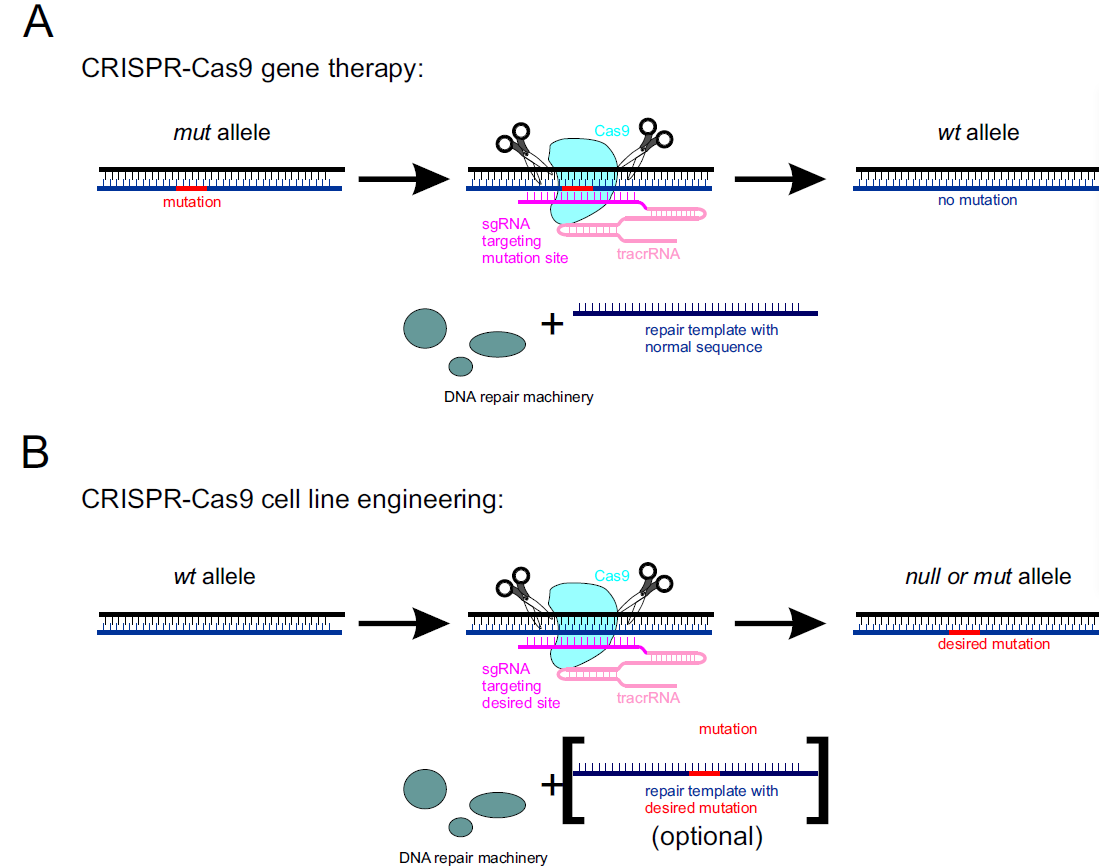

CRISPR-Cas9 can be used to reverse harmful genetic mutation in the human genome. This approach requires Cas9 protein, tracrRNA, and site-specific sgRNA together with the repair DNA template containing wild-type sequence. Cas9 creates a site-specific DNA break that is subsequently repaired by host DNA repair machinery, restoring wild-type allele (Figure 2A).

CRISPR-Cas9 can also serve as a reliable tool in cell line engineering. Cas9 creates a site-specific DNA break that is repaired by host DNA repair machinery. In the absence of a repair template, it can lead to truncations resulting in null mutants. A more targeted approach is available by introducing repair templates containing the desired mutation (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Use of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in A) gene therapy, and B) cell line engineering.

Future avenues

Editing nucleases have revolutionized genomic engineering, allowing easy editing of the mammalian genome. They are commonly used not only in basic research but also in pre-clinical and clinical studies as a potential mechanism to reverse DNA-based disease-causing mutations in inherited genetic diseases. Non-commercial and commercial innovations have allowed continuous development of technologies that started only 20 years ago, and they will be even more widely used in the future in advancing science and biomedicine.

Posted by Dr. Karolina Szczesna, Senior Product Manager and Technical Support at Proteintech Ltd.

Last edited in 2023 by Nicole Lynn, PhD Candidate at University of California Los Angeles

References

- Zhang, H-X., Zhang, Y., Yin, H. Genome Editing with mRNA encoding ZFN, TALEN, and Cas9. Mol. Ther. 27, 735-746 (2019).

- Khan, S.H., Genome-editing technologies: Concept, pros, and cons of various genome-editing techniques and bioethical concerns for clinical application. Molecular Therapy- Nucleic Acids, 16, 326-334 (2019).

- Kim, Y. G., Cha, J. & Chandrasegaran, S. Hybrid restriction enzymes: zinc finger fusions to Fok I cleavage domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 1156–1160 (1996).

- Christian, M. et al. Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases. Genetics 186, 757–761 (2010).

- Mali, P. et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339, 823–826 (2013).

- Cong, L. et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 (2013).

- Huang, X., Yang, D., Zhang, J., Xu, J., & Chen, Y. E.. Recent Advances in Improving Gene-Editing Specificity through CRISPR–Cas9 Nuclease Engineering. Cells, 11, 2186 (2022).

- Cermak, T. et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e82 (2011).

- Szczepek, M. et al. Structure-based redesign of the dimerization interface reduces the toxicity of zinc-finger nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 786–793 (2007).

- Ramalingam, S., Kandavelou, K., Rajenderan, R. & Chandrasegaran, S. Creating designed zinc-finger nucleases with minimal cytotoxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 405, 630–641 (2011).

- Zhang, X.-H., Tee, L. Y., Wang, X.-G., Huang, Q.-S. & Yang, S.-H. Off-target Effects in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Genome Engineering. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 4, e264 (2015).

- Maji, B. et al. Multidimensional chemical control of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 9–11 (2017).

- Chen, J. S. et al. Enhanced proofreading governs CRISPR-Cas9 targeting accuracy. Nature 550, 407–410 (2017).

- Kleinstiver, B. P. et al. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 529, 490–495 (2016).

- Slaymaker, I. M. et al. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science 351, 84–88 (2016).

- Murugan, K., Babu, K., Sundaresan, R., Rajan, R. & Sashital, D. G. The Revolution Continues: Newly Discovered Systems Expand the CRISPR-Cas Toolkit. Mol. Cell 68, 15–25 (2017).

- Tsai, S. Q. et al. Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI nucleases for highly specific genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 569–576 (2014).

- Qi, L. S., Larson, M. H., Gilbert, L. A., Doudna, J. A., Weissman, J. S., Arkin, A. P., & Lim, W. A.. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell, 152, 1173-1183 (2013).

- Ribeiro, L. F., Ribeiro, L. F. C., Barreto, M. Q. & Ward, R. J. Protein Engineering Strategies to Expand CRISPR-Cas9 Applications. Int. J. Genomics 2018, 1652567 (2018).

- Gilbert, L. A. et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell 154, 442–451 (2013).

- Konermann, S. et al. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature 517, 583–588 (2015).

- Liu, X. S. et al. Editing DNA Methylation in the Mammalian Genome. Cell 167, 233-247.e17 (2016).

- Vasquez, J.-J., Wedel, C., Cosentino, R. O. & Siegel, T. N. Exploiting CRISPR-Cas9 technology to investigate individual histone modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e106 (2018).

Related Content

How to solve the genome DNA damage

Epigenetics Modifications - DNA methylation

Epigenetics - DNA layers and chromatin modeling

Using Flow Cytometry with Epigenetics

Support

Newsletter Signup

Stay up-to-date with our latest news and events. New to Proteintech? Get 10% off your first order when you sign up.